Yesterday began per my usual Sunday; opening one eye at a time to check for life. I was grateful to discover my limbs fully functioning. I used them to move my cadaver beneath a hot shower. After putting on clothes to avoid unnecessary complications with the neighbors, I stepped outside into a beautiful summer morning. The out-of-control Morning Glories tried to trip me going down the steps, but I didn’t let it bother me. After all, per my usual Sunday, I get to play music.

My cheerfulness thusly restored, I appeared at the Aster Café on the river, and was greeted by the smiling faces of the staff there. October will mark five years Patty and the Buttons have held down the job of playing brunch in the establishment, so we’re all together in the cause. The man with the colorful Mohawk who strides the boards is one of the best barkeeps with whom I’ve ever had the pleasure to work. Troy and his cohort Del are instantaneous with the mocha with which I start each Sunday. Troy moves with the speed of an object in an elapsed time photo film. You have to use the kind of care with your gestures one might reserve for an auctioneer; a single raised eyebrow will make a scone materialize before you even knew you needed one.

It may be tough some Sunday mornings to make our way down there, but it’s a great job. I love sitting on that stage with my young boss, accordionist Patrick Harison, and my fellow Buttons, Keith Boyles on bass and Mark Kreitzer on guitar and banjo. We’ve been playing together long enough now—nearly seven years—that we aren’t just tossing out songs like a pitching machine. We’re constantly striving to be a tiny jazz orchestra, which supremely suits my sensibilities. I love the improvisation, but I love our set pieces equally well.

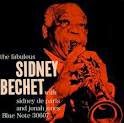

On this Sunday, Myra, the leader of Miss Myra and the Moonshiners, sings a couple with us. “Ain’t Misbehavin’” and “Blues My Naughty Sweetie Gives To Me.” Sam Skavnak, clarinetist for Miss Myra, sat in for our short final set. In addition to the Buttons repertoire, I got to play songs today like “Singin’ The Blues,” “Blue Again,” and “Stars Fell On Alabama.” Just a good ol’ Sunday.

From there, I went home to fancy up a bit. The Southside Aces were hired for what I kept calling a “society job.” A couple hours later, I and my black suit were moseying through the front door of the Louis Hill House, 260 Summit Avenue in St. Paul. The place was built in 1902 as a wedding present to Louis from his dad, James J. A decade later, Louis added what amounts to another mansion on to the front of the house. The kind of joint where the center hallway has more square footage than my whole apartment. Near the other end of this hall was a life size statue of a ballerina. She had plenty of room. In my house, we’d have to hang our hats and coats on her extended arms to justify her existence. Next to that was a living room where I began to set up. I kept thinking about Erik’s sousaphone when I looked at fragile crystal lamps and vases. I’m sure any catastrophe could eventually be worked off doing the dishes.

The event was a fundraiser for the Madeline Island Music Camp, dedicated to providing intensive classical music instruction. We were to be handsomely paid for a single hour of work. I had been impressed by Thomas George, the man who hired us, because he asked for us to play hot jazz, but to temper it with the sweet. “Hot and sweet” is familiar, historical terminology used to describe our music, but I’ve never before had a client specifically request it in that fashion.

About this time Nancy, our hostess, descended from upstairs in full gown. I already knew what she looked like from several portraits of her and her family hanging on the walls of the center hall. Whoever the painter was was good enough to capture the combination of mischief and steel that both reside in her eyes in good measure. We chatted looking out the front door. She joked about the summer heat, and implored me to take my coat and tie off. I didn’t. In the next breath, she made sure of a couple of performance details in a businesslike tone. I liked her. She was gracious, funny, a little high-societally naughty, but was very clear in communicating what she wanted, and making sure things got done.

I had Steve Rogness on trombone. He was the next Ace to arrive. I stood at the front door and was able to point and say, “Go all the way down the hall and take a left at the ballerina.” The others taking a left at the ballerina that day were Dave on drums, Erik and his crystal-endangering sousaphone, Henry Blackburn and his bristling trio of reeds, and Butch Thompson on piano. When Dave saw where we were playing he said, “That’s nice. I get to play on the good rug.” When Henry was walking up the driveway, about thirty feet away, he didn’t realize that the woman standing next to me was our hostess. He yelled, “Are they going to let us in the front door?” She paused before answering. I swear I could actually hear the gears of her graciousness grinding into place, and she merely beckoned to him to enter. About twelve feet away he still didn’t realize to whom he was addressing his comments. He later told me he for some reason thought it was Claudia standing next to me when he added jovially, “The Hostess with the Mostest!” Ah, these low-down jazz types.

We were all there except Butch. She asked who would be playing piano. I told her, and she swooned with excitement. Then she pointed at the baby grand in the living room and said, “I feel bad that this isn’t my best Steinway.” To her everlasting credit, she immediately laughed and said self-mockingly, “Oh, my life is so hard that I can’t provide my best Steinway.” But it was true. She instructed all of us to go upstairs to the ballroom just to look around. Part of the 1913 addition, the ballroom itself boasted of 3,000 square feet. It was here we counted four or five more grand pianos, tucked here and there in corners and up on the stage. The house was lousy with Steinways. The infestations of the rich.

It was time to begin. Our hostess had been looking after my comfort when earlier imploring for me to remove my coat and tie. This had to do with my first playing station. Thomas had told me Nancy had put in the invitations something to the effect, “Arrive to the seductive sounds of the clarinet.” While the rest of the band started the cocktail hour set inside, I would play by myself outside, joining them after about twenty minutes. I had been joking all week with the fellas about that one. The band was all sitting in place, talking quietly, when I stood, hitched up my pants with exaggerated gusto, and said, “Well, time to go be seductive.”

It was hot out. But despite the invitation of our hostess, and the possibilities of seduction such action may have encouraged, I would not remove any clothing. Obviously, this was to maintain my appearance of high class. I still, however, enjoyed myself out there. I played “Honey Hush,” “Stardust,” “My Blue Heaven,” “Quincy Street Stomp,” (I’m not certain of the seductive qualities of a stomp), and “Where Or When,” the sound carrying out past the joggers on Summit Avenue. I then rejoined the rest of the band to the left of the ballerina.

Steve asked me if I had managed to be seductive. I said, “Well, they all came into the house didn’t they?” Henry quipped, “Are you sure it wasn’t to escape the sound of the clarinet?” We settled into playing, nothing too strenuous. We would heat it up and bring it down, showing nice restraint and dynamics. During our set, an elderly gentleman came up to us just loving our music, and Butch’s playing especially. He said, “You know, this music reminds me of about twenty-five years ago when I hired a piano player for a party. I wish I could remember his name.” Henry said, “Was it Butch Thompson?” The guy, standing just eighteen inches from Butch, wrinkled his eyebrows which we interpreted as a no, so we suggested Rick Carlson. He said “That doesn’t sound familiar. It was definitely a jazz pianist, though.” Henry repeated, “Was it Butch Thompson?” which made me snort, because all this time Butch was silently looking at the man waiting for him to answer. The man brightened. “Butch Thompson! That’s it!” Henry pointed at Butch, “There’s the man himself” which gave a start to our fan.

The man himself provided perhaps my favorite musical moment when I had him start “Careless Love” solo. That man does all right on the piano. Henry and me on “Goodbye, Don’t Cry” was also pretty high in my rankings. Afterwards, packed up and on the sidewalk out front, I talked with Erik and Steve. Steve said, “I wonder if I somehow came into millions of dollars if it would even occur to me to have my portrait painted.” Offering no explanation, Erik said, “Probably.”

I went back home to fancy down a bit. I ate a sandwich and put on jeans and a tee. I hiked the mile or so over to Palmer’s Bar. It has been there that Miss Myra and the Moonshiners have been holding forth on Sunday evenings for a couple months now. At the beginning of my Sunday, I specifically planned on wanting this juxtaposition of experiences, the Louis Hill House to Palmer’s Bar. Palmer’s, of course, is significantly rougher. “Sorry, We’re Open” says the sign outside. The shoals of Palmer’s Bar make it far too easy to sink your ship. But it is a pretty colorful island on which to become shipwrecked. When I arrived, much of the humanity was gathered outside to stare at the blood moon coming on the heels of the lunar eclipse.

I urged Sam to get Myra to introduce them as “Miss Myra and the Blood Moonshiners,” but she wouldn’t bite. The band served up the music, and Seneca, the bartender, served up the bourbon. Even though it had been three weeks since the last time I was there, she remembered my order. She snickered at me and said, “I saw you looking over everything as if you weren’t going to end up with the same as usual.” I replied philosophically, “A man owes it to himself to know what his options are.”

The music is drawn from the repertoire of early jazz and blues, a lot of songs out of the Firehouse Five fake book. A girl named Angie has learned some drums to be in this band. A boy named Luke plays electric bass. On electric guitar is Zane Palmer. Jeanine, or “Red,” is Myra’s sister and plays trumpet. Sam, of course, on the clarinet. Myra plays rhythm guitar, sings and leads the ensemble. They are a spirited bunch, attacking music some of which was eighty years old before they were even born. They are rough and unpolished, but possess the charisma of earnest youth. I like them. I want them to succeed.

Then there’s the rest of the Palmer’s landscape. A mountain of a Native American man in a Minnesota Viking’s shirt stood in the middle of the bar with a slide whistle trying to play along with the band. He was terribly out of tune and loud. I was trying to figure out the non-judgmental, personally safe way to get him to stop when Cindy, Sam’s mother, just walked up to him and told him he was being rude. Just like that he ended his solo work. I think the force of Motherhood caused his obedience. But from somewhere I don’t know he produced a pair of bones he claimed were from a buffalo, and began to beat out rhythm on his thigh. This was not so intrusive, so everyone got to be happy. It did make me wonder what other weird instruments he had on his person.

A black man with dreadlocks tried to get up a dance with a woman. I think she had actually come in with him, but then pulled out the rug. She sort of sarcastically moved her hips for about seven seconds, then abruptly turned away and walked through the back door out to the patio, leaving him standing in the middle of the floor. I gave him a loud, sympathetic “Awwww!” He came over to me and said, “Man! I just hate to use a cliché, but that’s the story of my life!”

I dispensed unasked for music advice to the young kids that are Miss Myra and the Moonshiners before they headed out at the end of the night. In the bathroom before I left, I ran into a handsome black man in his thirties, wearing a porkpie hat. He said his last name was Brunious. I said, “Like the New Orleans music family?” He proceeded to name off Wendell, John and others of the family, surprised I knew of them. “I don’t have any of the trumpet skills of my father or anything, but I know about music. I’m trying to help these kids.” Of course I run into a Brunious in the bathroom at Palmer’s.

And what of these “kids,” these Moonshiners? They sure are being looked after by a lot of folks. Brunious, Papa John Kolsted, me and others. It’s like they’re an orphaned jazz band in the perilous Jazz Woods, and we’re a bunch of adult Jazz Bears making sure they survive. Whether they want or need our protection or not.

I jumped in a cab. I was full of whiskey, song and thoughts of egalitarianism. That pretty much describes a career in music. I handed out my card in three different places today. To a swing dancer in a middle class river café. To a woman wearing a dress that probably cost as much as six months of my rent, in the middle of her richly appointed living room at one of the Summit Avenue mansions. And to a man trying to live up to the expectations set by the many generations of his New Orleans music family, in the men’s room of a dive bar. Meanwhile, the moon looked down on all of us while it went about it’s business of eclipse and blood.